Essex, May 68 - a personal memory

"Here, this one will do!" I remember hearing, as several pairs of police arms grabbed me. I was 22, frightened but defiant; I hadn’t done anything!

It was 7 May 1968, my second year at the University and this was a day which would long be remembered.

"No arrests!" shouted a voice and dozens of fellow students pulled at the police till I was freed. Breathing liberty once more, I’d only gone a few yards before being grabbed and freed again.

How had it come to this?

During the 1963 Reith Lecture Series, A University in the Making. Vice-Chancellor Albert Sloman lauded his vision of how “a general assembly, trained university administrators and student councils will lead to success in the attempt to create the newest form of community of learning.” This was to be the University of Essex.

Upon enrolment in 1966, the campus, with its tower blocks, Alphaville type corridors and Hexagon Restaurant, felt as quiet and pedestrian as any university of the mid 1960s. This kind of continued for much of my first year.

Even then, the beginnings of dissent were becoming evident. On Saturday nights, after the dance, there had been spot checks to try and stop, male and female students sharing tower block rooms. Paralleling Nanterre in Paris, we resisted.

Around the world, there were stirrings. The sixties had already brought a revolution in music and this was spreading to other areas. Opposition to the war in Vietnam, the bomb, apartheid, civil rights in the US and Northern Ireland, African liberation, the iron curtain, the Prague Spring and more was helping to create a feeling that something was going on. It was the beginning a worldwide counter-culture.

Our parents couldn’t understand it. In the words of Bob Dylan

And something is happening here

But ya' don't know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

Everything changed with the new students who arrived in Autumn 1967, that same Autumn which followed the Summer of Love. You could spot it at a glance. Colourful clothes, Afghan coats and long flowing hair. And you could hear it - Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Ravi Shankar, Incredible String Band, The Doors and Country Joe.

By early 1968, discontent was continuing, unrest was brewing and questions were being asked about why Sloman’s vision of community was failing to materialise.

Protests and a restaurant boycott over food prices were leading to deeper questions about what the university was actually about, and who it was for.

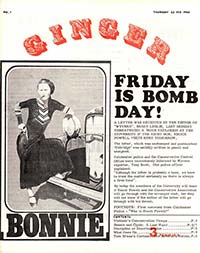

Fed up with the banality of Wyvern, the student newspaper, my good friend Ken Montague and I decided to create an alternative voice, a more radical voice. This was just becoming possible thanks to the development of offset litho printing. In one morning, walking around the shops in Colchester, we collected enough advertising money to pay for the first issue of Ginger.

Fed up with the banality of Wyvern, the student newspaper, my good friend Ken Montague and I decided to create an alternative voice, a more radical voice. This was just becoming possible thanks to the development of offset litho printing. In one morning, walking around the shops in Colchester, we collected enough advertising money to pay for the first issue of Ginger.

And we were in luck. We had a scoop! We found out about a bomb scare centred on the forthcoming visit from Enoch Powell, just a few weeks before his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech.

And we were in luck. We had a scoop! We found out about a bomb scare centred on the forthcoming visit from Enoch Powell, just a few weeks before his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech.

Partly because of the Ginger front page, the lecture hall where Powell was to speak, was packed solid. Andrew Pring, dressed as Guy Fawkes, had used a grapefruit and black paper to make a comic book bomb. He lit it and slowly walked towards the front of the hall and placed it in front of Enoch Powell. The meeting was in uproar with shout upon shout of ‘racist’. Powell decided not to continue, made his exit and was chased off of the campus by the student body.

Seven students were charged, including me. However, when we went to answer the charges, fellow students preventing the hearings from taking place. Large general meetings condemned the University for making the charges, and convincingly pointing out that all aspects of natural justice had been by-passed.

The first ever UK student sit-in was at University of Leicester at the end of February 1968. Now on a roll, after the Powell meeting, many of us wanted to show our solidarity. I packed about nine others into my Morris Minor van and we drove to Leicester. Driving through the Suffolk countryside, we passed through a sleepy little village called Steeple Bumpstead and had a good chuckle at the name.

On the way back, we stopped. We were in the middle of discussing whether the Steeple Bumpstead signpost might make a good memento of the day, when a car came round the bend behind us and went straight into the back of my Morris Minor van. Although my car was not noticeably any worse than it already was, the sleek, shiny car was seriously mis-shapen at the front.

Out of the car strutted a Colonel Blimp type, still in uniform, who started a tirade of "We fought the war for the likes of you" type comments. While he was insisting that it was all my fault, there slowly emerged from my van a succession of exceedingly hairy Essex types - Raffy, I think and Dane and Andrew Pring.

When the police arrived, I pointed out that my van had been stationary and the other driver should have been looking where he was going - conveniently ignoring that I had parked on a sharp bend.

The police started testing my van for roadworthiness. Hmm, there might be a problem. The handbrake wasn't actually working. They told me to take the van out of gear and then went to the back of the van to push. I quickly put the van back into gear so it wouldn’t move. As soon as they had finished pushing I subtly placed the the gear back into neutral. Phew! And they failed to notice the broken accelerator cable. I was driving using a piece of string connected to the throttle way under the bonnet, with still one hand free for the steering wheel.

We got back to the campus in time to see the evening news. The only students you could make out in the news coverage from Leicester were students from Essex!

Political activity among students continued. By the time the day came to protest in London against the Vietnam War, around 200 students from the University were to join the 17th March ‘Battle of Grosvenor Square’ demonstration.

And so to 7 May, that eventful day.

In the 1960s, not only were we terrified of nuclear weapons but also of the collaboration between with the UK and US to develop chemical and biological weapons. CS was developed and tested secretly at Porton Down and was being used against demonstrators worldwide, at the time just across the channel in Paris

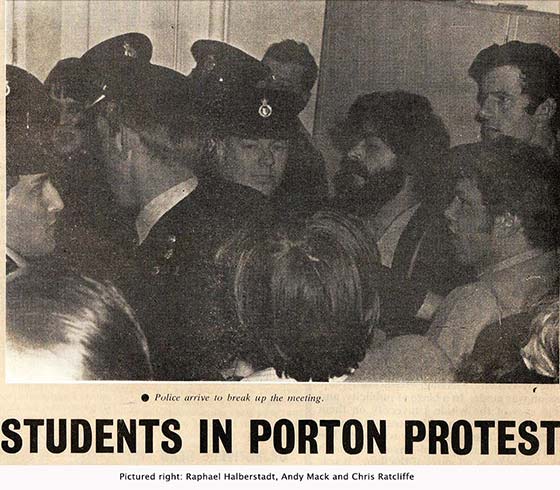

Dr. Inch, a scientist from Porton Down arrived to give a talk on toxic chemicals. The Chemistry Department had expected a handful of third year science undergraduates to attend the meeting. What they got was a 100 plus protesters armed with an indictment.

The planned demonstration had been organised in secret. Communication was by word of mouth and only to those people whose discretion could be relied upon.

Before Dr Inch could start speaking, Anna Mendelssohn stood up and started reading the indictment in a strong, loud voice. She described in some detail the activities of Porton Down; the development of Saren gas (a small dose of which will soon cause death after vomiting, involuntary defecation and urination, jerking, staggering, confusion and convulsions); the making of deadly genetic mutations of bacteria; production of chemical defoliants for warfare, etc.

University security men were soon on the scene. As fast as they prevented one person from reading the indictment, someone else would stand and start reading from another copy. Dr Inch was trapped and forced to listen to the charges.

The police arrived, bringing their dogs with them.

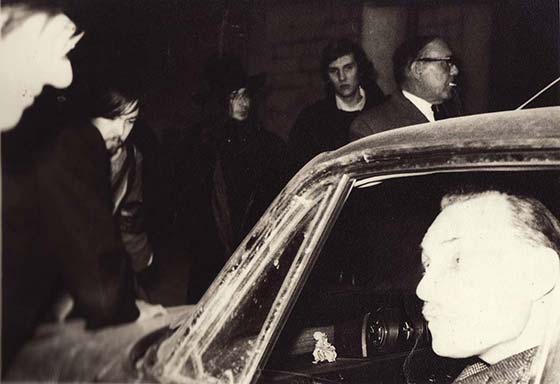

We all tried to retreat towards the residential blocks. It was at this point I was seized by the police, and released by my colleagues, chanting “Close Porton Down! Keep Science clean!”

In the following decade, student protest, sit-ins and occupations were to become commonplace. However, at this time, they were new phenomena and commanded national press attention. The following morning's papers were full of stories about the police and dogs being called to the Essex campus.

On Friday, 10th May three students, David Triesman, Raphael Halberstadt and Peter Archard, received letters of suspension. Ordering them to leave the campus by 6pm. Within an hour of the letters being delivered, a general meeting of four hundred students and staff had gathered. The Administration offices were occupied and the three students were hidden away for protection in one of the residential towers.

A delegation of about 250 marched to the Vice-Chancellor's lakeside villa. They demanded an audience with the VC, Albert Sloman, but his wife insisted that he was not at home.

Strong feelings, tension and excitement increased throughout the weekend. Newly painted slogans spoke for many.

The floor is now open to further questions

Where has all the knowledge gone? Long time passing

The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.

Monday morning saw the largest general meeting in the university's three and a half year history. Over a thousand staff and students were present; about four fifths of the entire university. A motion deploring the Vice-chancellor's action to arbitrarily suspend the three students, and his refusal to attend the meeting, was passed by a huge majority.

The meeting continued all day. Speeches were lively, impassioned, humorous and often, poetic. By the end of the day, it was agreed that all routine teaching and functions at the University should be suspended until the three students were reinstated.

The following morning saw the creation of the "Free University of Essex." Teach-ins, organised discussions and seminars were held on many of the issues that had been thrown up by the conflict. These included university reform, the role of the press and, of course, chemical and biological warfare.

Distinctions between staff and students became notably less obvious. The atmosphere was festive. In the evening the campus main square was packed with students clutching bottles of wine and dancing to the music of the time, including Country Joe’s anti-Vietnam songs. "One, two, three, four, what are we fighting for?”

Large general meetings, the Free University, media attention and negotiations with the VC and Senate continued all week.

By the Thursday, Dr Sloman finally agreed to attend the General Meeting and answer questions. If anything, attendance at the Thursday meeting was even larger than the Monday one.

However, Sloman's response was evasive, unclear and showed little grasp of the impact his actions had had. In the one and a half hours he was present, he failed completely to give reasons for what both staff and students saw as his arbitrary use of power. He failed to explain why the three students had not been given the opportunity to present their case. Or why there was no independent appeals procedure.

Even a report in that morning's Times had remarked, "...One can certainly sympathise with the students over the issue of justice. They were not asked to state their case nor are they allowed any appeal against the decision. Additionally, only three out of some 100 to 200 students were singled out for treatment." (Times, 16th May 1968)

Dr Sloman insisted that authority in the University, and therefore the three students' futures, rested with the Senate. The Senate had already met and endorsed the VC's actions. It was not due to meet again for another month.

Staff and students remained united, adamant and lyrical in their persistent demands for the students' reinstatement. Letters and telegrams of support flooded into the University, including one that was believed to be from Jean-Paul Sartre.

That evening, behind-the-scenes moves by senior staff were successful in bringing about a further meeting of Senate the next day. The tide was against them and Senate could no longer resist the almost unanimous feeling of the university community. A face-saving formula was worked out which meant that three students were immediately reinstated.

The demonstration over Porton Down and its publicity provoked results that could not have been foreseen. A founder of a group campaigning against chemical and biological warfare (CBW), contacted the University. She said that because of the protest, the Guardian had decided to publish a front page article on the subject. She had been unsuccessfully pressing them to do this for some time.

The BBC decided to show a film on CBW that they had made earlier. The Observer released a list of University scientists engaged on work connected with Porton Down.

Other knock-on effects from the Porton Down demonstration were, if anything, more important. The Free University debated issues such as the extension of university democracy, the validity of the examination system, the nature and purpose of knowledge and the concept of free speech. At the end of the summer term, when the students departed to their different parts of the country, many took with them the spirit, ideas and inspirations of their own May 68.

Only six months before the May 68 events, sociologists and pundits were stating quite categorically that workers and students had been contained within modern society. The age of revolt and protest, they would have had us believe, was merely a thing of the past.

Historically, students had been regarded as another part of the Establishment. They were the ones who did as they were told. If they had any association with politics in the public mind, it was as strike-breakers in the General Strike. 1968 changed all that.

Essex was the first British university to be shaken by a major revolt. The influence of the May 68 events, and the examination of the issues they raised, was not confined to those who took part. Our experience, and similar experiences across the world, was avidly followed, analysed and developed by a whole generation. This generation was part of a complete renaissance of ideas of the post-war world.

The Free University didn’t survive the summer. But the desire for change wasn’t going away. Forty students were arrested in a Vietnam demonstration in Colchester, clogging up the local magistrates’ court for months with our pleas of ‘not guilty’.

The Free University didn’t survive the summer. But the desire for change wasn’t going away. Forty students were arrested in a Vietnam demonstration in Colchester, clogging up the local magistrates’ court for months with our pleas of ‘not guilty’.

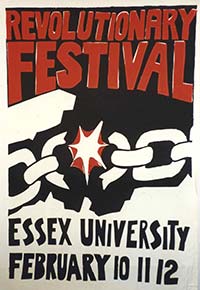

In February 1969, came the Revolutionary Festival with an event feminist writer, Sheila Rowbotham describes as "what appears to have been the first ever public Women's Liberation meeting in the UK”.

In Autumn 1969, the University threw out more students, leading to a barricading of the Senate.

Ken Montague was elected Editor of Wyvern on the back of Ginger’s success, and the two us took great pleasure in totally transforming the student newspaper.

Ken Montague was elected Editor of Wyvern on the back of Ginger’s success, and the two us took great pleasure in totally transforming the student newspaper.

In November 1969, the Court of Appeal reversed a previous High Court decision and granted the University an injunction against me entering the campus, after a 2 day hearing. An injunction which probably still stands. But that’s another story.

Consequently, when I am informed that most students are uninterested in politics and happy playing with their devices, I remember similar images of apathetic domesticity among my own contemporaries not long before the rebellions of 1968.

In spite of commentators consistently trying to undermine the achievements of those times, many of us have never lost our radicalism. On the contrary, it has deepened and matured. We’ve been part of the Green, Peace and Women's movements. We’re still campaigning against racism, poverty and pollution.

As John Lennon said, “The thing the sixties did was to show us the possibilities and the responsibility that we all had. It wasn't the answer. It just gave us a glimpse of the possibility.”

© Chris Ratcliffe