May 1968 - hitchhiking from Essex to Paris

Ce n'est qu'un début

Continuons le combat

I was immediately attracted to its rhythm, its music. I had no idea what it meant and it really didn’t matter. This chant is one of my abiding memories of many demonstrations in Paris 50 years ago during the events of May 1968. Repeated again and again and again. To a 22 year old student, the sound was enchanting, revealing the power of those who wanted justice and change.

“This is only the beginning. Carry on the Fight” was the the rather disappointing translation. Less colourful in English but in French its meaning went far beyond mere words. Embodying all the sensations, ideas and hopes of the time, it was everywhere. Find a YouTube video of a May 1968 demo and you’ll hear the infectious Ce n'est qu’un début . . .

Something big was happening in France. With rapid expansion of Higher Education, a large, new university had been created at Nanterre on the outskirts of Paris. Unrest had been simmering among the students, especially over segregated dorms. When the authorities shut down Nanterre University at the beginning of May 1968, thousands of students descended upon the Sorbonne, the University of Left Bank Paris. Now occupied by students from both universities, using the notorious CRS riot police, the authorities shut down the Sorbonne and evicted the students. A month of unrest, marches and barricades led to a general strike which soon encompassed the whole of France.

I was a student at Essex University where, like Nanterre, tension had been increasing for several months. Arbitrary student suspensions followed a protest against a visiting speaker from Porton Down. Attended by nearly all the University population, a huge meeting voted overwhelmingly to refuse to participate in the University - in its place, a Free University was declared. Our own May uprising!

At the same time, we knew that something momentous was igniting across the channel. What was happening in Paris felt like a logical continuation of events that had been taking place at Essex.

Back then, no-one had TVs in their room. We’d all crowd into the one ‘TV room’ to see those unbelievable scenes from France.

When friends and fellow students first started talking about actually going over to Paris, I had hesitated. Second year examinations were due to start in a couple of weeks. My friend Ken M looked at me and remarked, "You know, I think if you don't go, you might regret it for the rest of your life." It was true. I had to go.

That evening, soon after the news had ended, half a dozen of us were packing our bags. Three of us arrived at Chris T’s house in London around three in the morning. My lasting memory is of her furious father screaming that there would be no money for her next year at university.

Over-confident young hitch-hikers, we didn’t make the vague rendezvous of the "other side of the Dartford Tunnel at 9.30am" the next morning. However, we succeeded in meeting up on the boat that left Dover at one o'clock. Because France was in the grip of a General Strike, all ferries between England and France remained in port - this was more than 25 years before the opening of the Channel Tunnel. The only way of reaching France was via Belgium.

By five o’clock, Paul G and I were on the outskirts of Ostend with our thumbs waving.

Crossing the border into France, we were hit by the atmosphere, electric and festive. The whole nation seemed to have come alive. Everywhere we went, people were holding forth on some aspect of "les evenements". Our last lift, a Dutchman, stopped for some beers. The cafe was packed, and in uproar, with everyone shouting their opinions.

By two in the morning, we were in Paris. Our arrangement had been to meet at the Sorbonne, occupied by its students for most of the month. But when Paul and I arrived, the students were in the process of evacuating the building. There were several explanations given for this. Some said the police were about to attempt to re-take the Sorbonne. Others told us the buildings needed a good clean. Fears about right wingers was a third reason we were given and that the right wing of the student community was vicious and highly trained. They’d been beating up people and escaping quickly. Although we never saw any gangs of right-wingers while we were there, the French students took their threat very seriously. Several times, we were stopped by fellow students and asked for our papers when the explanation were given was that they were worried about "fascists".

The Paris students were well organised; they arranged security and welfare. First leading us to the Faculty of Science, they indicated where we could unroll our sleeping bags. It was a physics laboratory and we were advised not to go out again that night because the police were outside, beating up anyone they came across. Throughout the night, people would return with tales of these beatings.

The following morning we strolled round the Latin Quarter. Wherever we looked, there was a crowd of people debating, disputing and yelling with each other. Everyone wanted to join in. The now iconic posters and slogans were plastered over every available wall space:

We are the children that our parents warned us against.

We are all German Jews

The more I revolt, the more I make love

Imagination usurps power

Sous les pavés les plages

Soyon realistes - Demand l’impossible

Travailleurs de tous les pays - Amusez vous

All the newsagents were on strike, so daily newspapers had to be sold on the streets, alongside Enragé, Rouge and Le Canard Enchainé. Temporary bookstalls had sprouted up every few yards with the new rebel literature: the writings of Marcuse, Sartre, and pamphlets by such groups such as the Situationist Internationale. The whole length of the Boulevard St. Germain was transformed into a permanent flea market. We’d never seen anything like it.

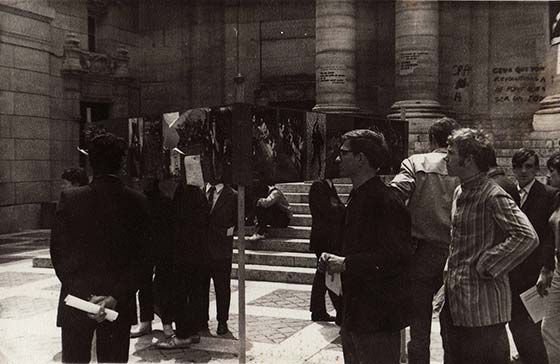

Mai 1968 - Sorbonne. Photo: Paul Goodchild. Click to enlarge

The occupied Sorbonne was open again, full of exhibitions about the disturbances. Buildings and courtyards were colourfully packed with people in sixties students clothes, red and black flags and yet more slogans.

Mai 1968 - Sorbonne. Photo: Paul Goodchild. Click to enlarge

Outside the Odeon theatre, a large `EX' had been painted in front of the sign "Theatre of France". Here too, red flags adorned the building. Inside, was an open-ended debate that went on twenty-four hours a day. Anyone could enter and anyone could speak. Permanent democracy in action.

We were told tales of how the police had even gone into hospitals to beat up the injured. The distinction between guilty and innocent became blurred. Passers-by, pregnant women, reporters and members of the Red Cross all became victims.

Over thirty students from Essex visited Paris during May 1968. One of them, Andy M., was arrested, beaten and held for 24 hours. For much of this time, he was kept in a barbed pen in the rain. Upon his return, he told the student union newspaper that he was surrounded by "many bloodied figures.”

We were disappointed to learn that there was no demonstration planned for that day. Nevertheless, at about half past six the CRS, the hated French riot police, started encircling the Latin Quarter. Vanload after vanload arrived. Soon after, they began firing their CS gas. There had been no demonstration, no student provocation and we could not understand why there was suddenly this amazing police assault. It was apparently part of the regular nightly pattern.

Student members of the Faculty of Medicine had described to us the harm the gas could do. One girl had been blinded and many others had complained of liver and chest problems. Prolonged contact could be toxic. However, the main danger, as we soon learned, was the firing of the gas canisters at point blank range instead of into the air. The exploding canisters led to all forms of serious injury. And where was CS gas developed? Porton Down.

The Britain of the 21st century is rather more accustomed to the sight of riot police. But 50 years ago, we could still be shocked at row after row of armed CRS in full riot gear and helmets, brandishing long clubs.

A Sunday Times reporter wrote: "What shocks the British observer in Paris is the evident relish with which the CRS engage in acts of wanton brutality against bystanders, the wounded, the unconscious, the old, the vulnerable." (Sunday Times, 26 May 1968)

Contrary to the impression given by so much of the English media, members of the student organisation actively tried to prevent fighting breaking out. They advised people to save their energies for the "grand manifestation" planned for the following night, 24 May. Gas canisters continued to land all around.

Barricades were hastily erected to hold back the police attack. Anything that was movable went into these barricades. Cars, iron railings, paving stones and trees were passed along great chains of students. The barricade would be ignited and another one built a hundred yards further on.

On Friday evening, 24th May, we went and joined the massive demonstration which was gathering at the large square near the Gare de Lyon. Hundreds and hundreds of thousands of workers, students and all types of different people turned up. I had never seen so many in my life. The square was totally full, as were all the wide boulevards which approached it.

Eventually, the demonstration moved off. There were too many people for just one march. It broke into different demonstrations moving through the streets of Paris. We sang the "Internationale" and chanted "De Gaulle, Assassin", "CRS SS" and of course the rhythmic, "Ce n'est qu'un debut . . .”

We found ourselves moving towards the Bastille and began to believe we were about to storm it again. The police were taking no chances. The road was completely blocked by an army of them. Automatically, the demonstrators started building a barricade and again, trees, bricks, paving stones and cars were piled together.

The police charged. We waited until the last moment because we wanted to take some pictures. And then we ran like mad with thousands of others. We had almost left it too late. Tear gas grenades were exploding all around us. I remembered the tales of serious injuries which had been caused by exploding teargas canisters. My legs were wobbling from fear, but eventually the police stopped and we caught our breath.

The thick gas was everywhere. Those not wearing masks held handkerchiefs to their mouths. At first I couldn't understand why water was being continually thrown down upon the demonstration by people standing on the balconies of their apartements. Now I realised. It was to dampen down the gas. This gesture of solidarity that showed that the demonstration was supported by most of those living in the city.

A group of people came running from the opposite direction to which we were going. Handkerchiefs were tied over their faces, but I recognised one of them. Dave C was another student from Essex.

"We've done it, man! We've done it! We've burned Le Bourse!” He explained how a group of about five hundred of them had set fire to this, the greatest symbol of French capitalism. (20 years later I failed to recognise Dave, his shoulder length hair long gone, when he arrived as the new vice-principal at the FE college where I worked.)

With so many on the streets and with so much obvious support from the people of Paris, there was a feeling that anything could happen that night.

The march was now heading towards the Latin Quarter. Only one bridge across the Seine was still unblocked by the police. The tens of thousands streamed across. As we crossed, every few seconds, the sky lit up and there was an almighty explosion.

The BBC cameraman I stopped to talk with was, like the rest of us, visibly frightened by these explosions. Was this the State fighting back against what might well have turned into an uprising? Were they trying to bomb the bridge? Just what might be going somewhere else in the city? Later, we found out that the loud explosions were some kind of super-thunderclap: harmless but terrifying.

Mai 1968 - Paris. Photo: Paul Goodchild.

The march headed towards the Sorbonne and the demonstrators once more set about constructing barricades. Every car in sight was used. As soon as one barricade was built, it was ignited. Work would begin on the next one. In this way, the Latin Quarter was defended by row upon row of burning barricades.

Everyone was preoccupied with the gas. The lucky ones had goggles to protect their eyes. The rest of us made do with handkerchiefs or masks over our faces. Even inside the Sorbonne, the gas was thick.

After an hour or two, Paul and I tried to make it back to the Faculty of Medicine, our base. But all the roads were blocked. The CRS were attacking from all sides. We were standing discussing what to do next, when hundreds of people started frantically running past us. A battalion of CRS were charging them. We ran too and again grenades were exploding all around us.

About fifty of us scampered into a block that had something to do with the students' union. After a while, we tried to leave, but saw that hundreds of police and their cars and vans were parked outside. It was about two in the morning and we were trapped there until seven o'clock.

A good atmosphere began to develop inside among people from different countries who had been drawn to Paris in the same way as us. From time to time, the CRS would bang on the door. Everyone would stop breathing, praying that they would not storm the building. At one point, they fired a gas canister into the hallway at the bottom.

After a couple of hours, we unsuccessfully tried to escape a back way. As we were attempting this, the people who lived in neighbouring apartements started shouting at us. "No! No! You are mad! It is much too dangerous. The police are everywhere. You will be beaten up."

It was too cold to sleep without a sleeping bag and anyway when I tried, the particles of gas became trapped between my eye and eyelid, causing intense irritation. Those who seemed to know about these things advised us not to eat or drink for four hours after inhaling the gas.

We listened to radio reports on what was happening in other French towns and in other parts of Paris. It was strongly rumoured that up to twelve students had been killed and hundreds injured. Many more were missing, having been arrested. Worried parents were frantically trying to trace their children.

Twelve hours later, over half the people walking around the streets of the Latin Quarter still had handkerchiefs or masks over their faces. The gas was thinner, but still very uncomfortable.

The next night we found some tables to sleep on at the Faculty of Medicine. Autopsy tables! When I woke up I was alone except for an "action committee" meeting going on all around me. I managed to get dressed and leave without being unduly noticed

A couple of days later, I returned to England and my exams. Hitchhiking back to the university campus, a respectable looking car pulled over to give me a lift. It was my parents! Long afterwards, my mum would tell of her horror the day they realised that the dishevelled, wild-looking student begging a lift in the middle of nowhere was her son. In vain, did I try to explain the intense experience I would never forget.

Who would have thought a few days in Paris 50 years ago could change my life in so many ways. Not least, I became a francophile and learned the language. I didn’t know much French. I had wanted to learn it at my secondary modern school but our teachers refused.

My most lasting impression was not, in fact, the barricades, the CRS or the tear gas. It was the feeling of excitement and coming alive in a way few had ever dreamed possible.

For the few weeks of May thirty years ago, people took control of their lives and let their imagination shine through. People from all walks of life had congregated in the boulevards, taken over their universities and factories and taken delight in discussing how things could be changed.

A whole generation had a profound experience of how very different our society could be. The glorious memory of that experience has stayed with us, guiding our lives. That, yes that, is the great and lasting success of May, 1968. Vive les soixante-huitards!

© Chris Ratcliffe, updated April 2018